The Cooperative: A Theory of Ownership

What, or who, makes a firm?

Prologue

In The Ownership of Enterprise, Hansmann reimagines the business corporation as a framework of cooperation and transaction between different market actors that to explain more “traditional” theories of corporate ownership and control. Hansmann provides a compelling account of different stakeholder and market actors involved in and around a business organization, whom he labels patrons; they include customers, suppliers, workers, and investors. Furthermore, Hansmann’s framework of ownership places particular emphasis on the pivotal role of transaction costs in the arrangement and organisation of a business entity to explain how the rights to control and rights to residual earnings are shared or controlled by various patron groups. Through this framework, Hansmann compellingly argues that business corporations–even traditional investor-owned corporations–are in essence cooperatives by virtue of their ownership structures. This essay aims to unpack Hansmann’s key claim through an evaluation of his framework of ownership and analyze the moral implications of his theory of ownership.

A Capital Cooperative

Hansmann begins by first identifying and separating the many actors that transact within and without a firm into distinct patron groups, which he identifies as customers, workers, suppliers, and investors. While investors that pool and provide capital have traditionally been associated with ownership and control, Hansmann asserts that the conventional investor-owned business enterprise is nothing more than a cooperative of capital lenders that engage in cooperation the same way that worker and supplier cooperatives pool input to engage in market activity. The key to Hansmann’s claim is that investor-owned cooperatives essentially share the same structures of ownerships with other forms of cooperatives in the sense that the rights to control and pecuniary profits belong to whichever patron group that pools inputs–or even consumption, in the customer cooperative case–to form a business enterprise.

Essentially, Hansmann’s argument is as follows: how is a dairy cooperative that consists of farmers pooling milk different from any other corporation funded by the pooling investor capital? It isn’t. Under Hansmann’s framework of ownership centred around the rights to control and residual earnings, the dairy cooperative is no more different to the investor-owned corporation than it is to any other cooperative form. Just as the dairy farmers “sell” milk to the cooperative at a steeply discounted price as a “loan” in return for voting rights and potential future profits, investors bear the risk of providing capital in the form of interest free loans in return for the rights to control management and future residual earnings. Hansmann even goes as far as to argue how there is no fundamental reason why investor-owned corporations cannot be formed under cooperative corporation statutes instead given how they are in principle no more than specific forms of cooperatives. Therefore, the investor-owned enterprise is as much of a cooperative as any other type of cooperative–the only difference is the pooling of capital instead of labor, milk, or any other input; the supply of capital to the firm in a transactional exchange for ownership no more special or different than the supply of labor or any other input to form a “traditional” cooperative.

Who Owns What?

Once it has been established that investor-owned business enterprises are nothing more than specialised cooperatives, Hansmann uses that framework to construct a theory of ownership to explain two key problems: firstly, why is ownership more often than not attributed to the firm’s patrons? And secondly, what factors determine which particular patron group assumes ownership? And in particular, why is it that investor-owned firms have become the default as opposed to other forms of cooperatives? To answer those questions, Hansmann delves into the pivotal role of transaction costs in the relationship and choice between market contracting and ownership.

To answer the first question, Hansmann explains that there is no necessary requirement for a firm to be owned by its patrons. In principle, a pure entrepreneur could acquire capital solely from borrowing while purchasing inputs and selling products on the market all without forming a cooperative of any kind. But an arrangement of this kind is exceedingly rare, not least because hardly many entrepreneurs can sustain a large corporation without resorting to some sort of cooperation to maximize efficiency and minimize risk. And even more rare is an arrangement whereby more than one patron group shared ownership–the competing interest of different patron groups rarely makes a good recipe for cooperation.

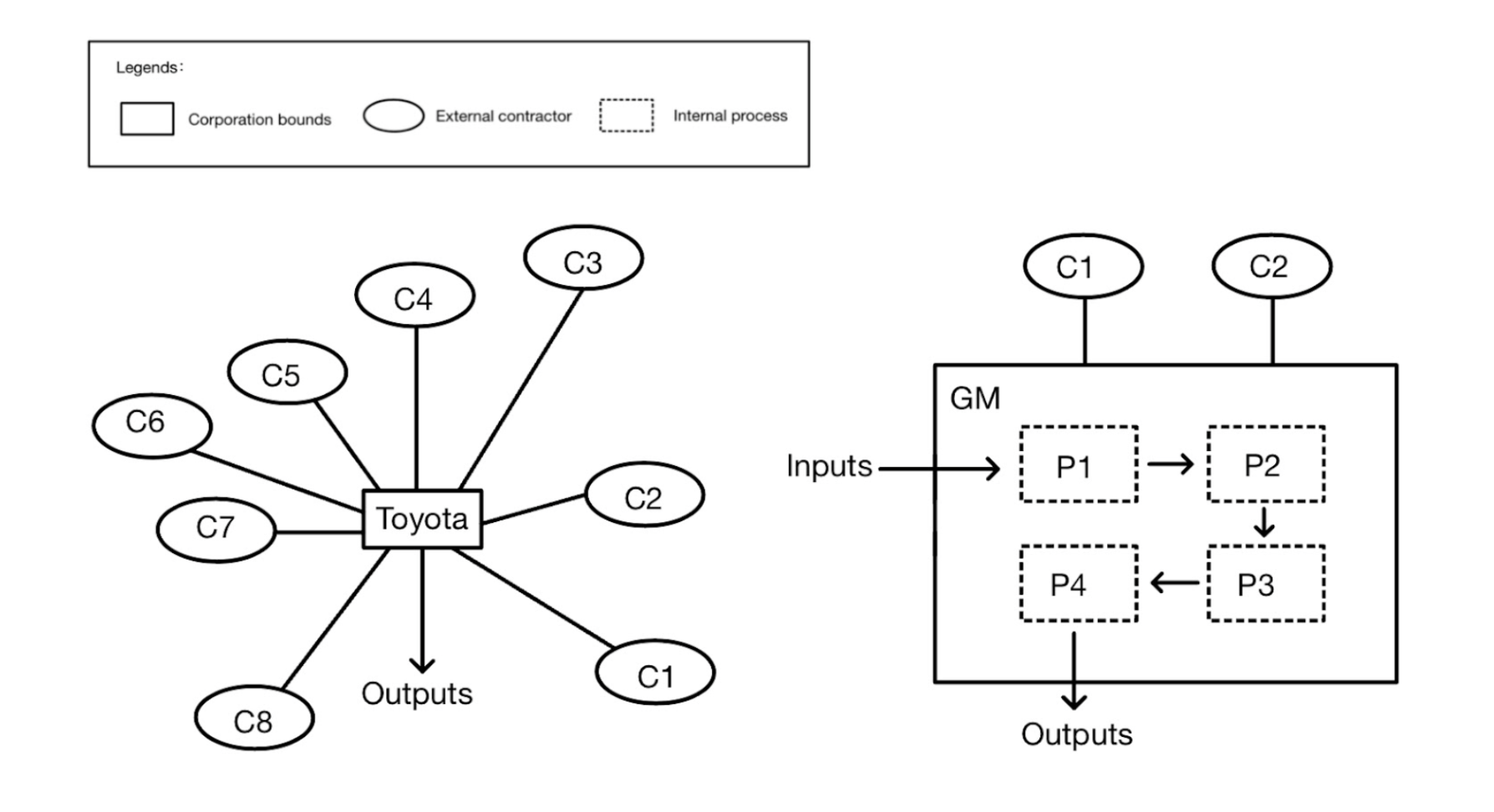

Figure 1.

To answer the second question, Hansmann envisions the firm through two forms of transactions: market contracting and ownership. As a nexus of contracts, or a signatory that engages in market transactions through contractual interactions with other market actors such as financial institutions or other suppliers, the firm engages in market activity outside of its governance and ownership. In Figure 1, Toyota the corporation is imagined and illustrated as a nexus of contracts by relegating all production processes to outside contractors through market contracting; it is nimble and “lean” but reliant and subject to the mercy of outside contractors it cannot directly control, except through means of negotiation and contraction. Alternatively, firms can also engage in “in-house” activity by exercising the levers of ownership to engage in market activity. To illustrate, General Motors is depicted in Figure 1 to own almost all of its production processes and inputs from carburettors, fuel tanks, paint jobs, to windshields and everything in between that goes into its automobiles; it is capital intensive, “heavy,” and certainly less nimble than its Japanese counterpart, but exercises a far greater degree of control and autonomy over its production processes. This distinction and choice between ownership and market contracting serves as the foundation for Hansmann’s construction of a theory of ownership.

Hansmann also identifies the central role of transaction costs associated with both market contracting and ownership in determining which patron group assumes ownership, and distinguishes two general forms of transaction costs, namely costs of ownership and costs of contracting. He argues how the cost minimising tendencies of business enterprises operating in markets naturally allow and encourage the size of these costs to dictate the assignment of ownership among different patron groups. Just like any other market actor, a firm is naturally inclined to achieve Pareto optimality to the best of its abilities through revenue maximisation and cost minimisation, and as such it only makes sense that the assignment of ownership is no more than a strategic response to the complexities of managing economic transactions within an enterprise.

Costs of ownership are generally attributed to the inevitable complexities and difficulties of exercising control over a firm. In an enterprise where ownership and control are not exercised simultaneously by the firm’s owners, these can include costs of hiring and controlling managers to ensure their fiduciary obligations are upheld. Failure to exercise effective control over managers may lead to managerial opportunism, another cost of ownership in its own respect. For example, Enron’s board of directors and shareholders simply failed to exercise effective control and oversight over its managers, and therefore paid the price–or cost–when it was revealed that management cooked the books and egregiously misled investors. In large firms, the heterogeneity of opinions and interest among owners may translate into costs of collective decision making; even in large firms where interests and opinions are relatively homogenous, the logistical process of decision making among a large number of owners is often a costly process. Factory workers may seek higher wages and enhanced benefits that tighten margins and hurt the bottom lines that dictate the size of C-suite bonuses. When those workers go on strike and halt production, investors and managers pay that cost of managing a firm comprised of patrons with competing interests.

While ownership costs can rack up in large firms where owner-patrons have a variety of interests, ownership also represents a reprieve from the costs of market contracting, which can sometimes far outweigh ownership. When firms engage in external market contracting with other non-owner patrons, they do so under the premise of an adversarial relationship. In cases where the adversarial relationship of market contracting results in extremely high costs, the invisible hand of the market often nudges patrons towards the more efficient path of ownership instead. Contracting costs can easily become the benefits of ownership through the formation of cooperatives, while the opposite can also be true: ownership costs within an inefficient governance structure can easily be negated through market contracting.

A Complete (Hansmannian) Theory of Ownership

Therefore, according to Hansmann’s theory of ownership, the assignment of ownership is a reflection of market forces that incentivise the optimisation of both market contracting costs and ownership costs. Applying this framework to the mystery of why investor-owned firms have overwhelmingly dominated the market naturally points to the conclusion that investors are simply the best-positioned patron group to minimise the transaction cost of a business cooperative. Hansmann attributes this to the relative homogeneity of investor interests even in large ownership structures; rarely are investors more interested in anything other than profits. After all, what is more homogenous than cold hard cash? Certainly not milk or labor.

Moral Implications

Given that Hansmann’s theory of ownership arrives at the conclusion that traditional investor-owned corporations are just mere capital cooperatives not so different from the ownership structures that define other forms of cooperatives, the premise on which he arrived at that conclusion is particularly salient with regards to the morality of profit-driven, investor-owned firms in competitive markets. Considering the contentious subject of corporate profits and its fashionable association with greed and immorality in contemporary literature and debate, Hansmann’s reconstruction of the investor-owned corporation as a cooperative held together by an ownership structure guided by transaction cost efficiency flips the script in the ongoing debate on the morality of profit-driven entities that serve the interests of investors. Rarely is there discussion on the immorality of dairy producer cooperatives like Gay Lea or consumer cooperatives like Mountain Equipment Cooperative, not by virtue of fact that they are not profit driven (they are) or that their ownership structures are fundamentally different from that of investor-owned cooperatives as Hansmann has shown, but simply because they are not investor-owned.

Hansmann’s conclusion has two broad moral implications: firstly, if investor-owned corporations are in practice and principle capital cooperatives not so different from other forms of profit-seeking cooperatives, then perhaps the controversy and contention surrounding the profit-seeking behaviour of the former is misplaced and misunderstood. More importantly, Hansmann's analysis challenges a reconsideration of the prevailing narratives around the morality of profit-driven corporations. If, as he suggests, investor-owned corporations function as capital cooperatives with aligned incentives among shareholders, then the traditional criticism of these corporations as solely driven by profit motives may oversimplify their nature. Secondly, Hansmann's theory of ownership encourages a more informed and balanced discourse on the ethical dimensions of profit-driven corporations, urging a deeper understanding of their organizational structures and motivations. It is entirely plausible that the jus ad bellum discussion around the profit-seeking nature of market actor is overblown and misunderstood, and that the most salient questions of morality that rise out of markets lie in the jus in bello considerations of how these firms engage in how these firms seek out residual earnings.